| Hoon and Gee Chew Lin Owyang | ||

View the interrogation records

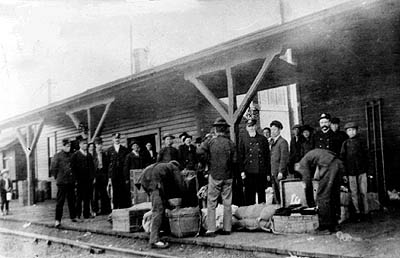

Sumas train station (from Customs and Border Protection website) Click to see these photos enlarged (the shot above is of the family around 1944; below is the family house in Courtland in 1934)

View current day photos of what's left in the store and nearby area.

This is the character for Owyang:

from seventh cousin, twice removed, Jeremiah Owyang's group website.

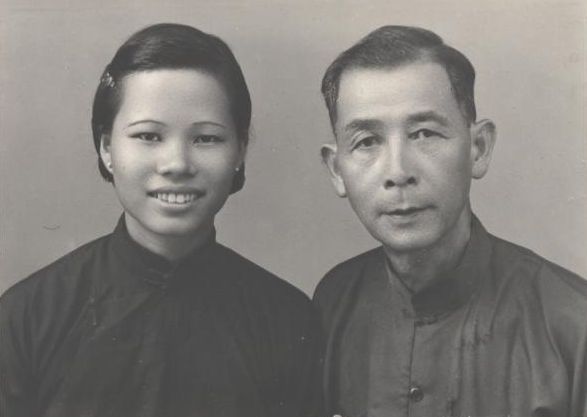

Hoon Owyang with his second wife, c.1948.

Goong Goong's family in Dai Liang village, 2006 when Grant and many cousins visited.

|

Hoon Owyang, also known as Owyang Koon Cheung, was born on June 12, 1878 in Dai Liang (also spelled Tai Ling) Village, Zhongshan (also known as Heong Shan) District, Guangdong Province, China. He died in October, 1963 in Oakland, CA, where he was buried. His father's name was Owyang Yee Bow (also known as Owyang Jock). According to The Historical Data and Genealogical Table of The Owyang Family For Four Thousand Seven Hundred Years, published in Dai Liang village around 1990, Owyang Yee Bow's father was named Owyang E Joe. His father was named Owyang Quock Ying, and his father was named Owyang See Mon. Owyang See Mon had four sons. Unfortunately, the main data presented is only on the sons of the family. Click here for further explanation and a segment of the chart that details our family information. His first wife Gee Chew Lin Owyang was

born in 1885 in Zhongshan, China. She died

in 1934 in California. She was buried in Franklin, CA. Hoon Owyang and

Gee

Chew Lin Owyang were married in China on April 21, 1917 and had the

following children: Owyang Yung Son, who was born in 1918 and died in

1919 in China; and Mary, William, Margaret, John, Louise, and Esther,

who were all born in the United States.

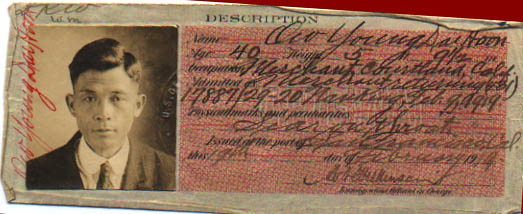

Hoon Owyang first arrived in North America on November 8, 1905, arriving in Vancouver, British Columbia on the S.S. Empress of China. Interestingly enough, our fifth cousin and genealogy researcher Michael Ho found a ship log with Hoon Owyang's name on it for the Empress of China's landing in San Francisco on November 12, 1905, with Hoon Owyang's name crossed out. He must have originally planned to sail to San Francisco but possibly talked to other passengers and decided to disembark in Vancouver. Historian Erika Lee, in her excellent At America's Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943, writes about how many Chinese immigrants came into the U.S. through Canada because the immigration service was far less strict than in San Francisco. Hoon Owyang then took the Canadian Pacific Railway to Sumas, Washington, where on November 18, he applied to land in the United States as a Chinese merchant of Yau Lan Moon, Canton (now romanized as Guangzhou). He presented a Certificate for Merchant, which verified his merchant status (because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, from 1882 to 1943 Chinese laborers were not allowed to immigrate to the U.S.; only merchants and other professionals, and their spouses and children were allowed). According to the GSA website, Twenty-four border stations were soon established including the earliest U.S. Customs House in Washington State which was located in a rented building at the Port Sumas in 1891. (Sumas, 20 miles inland from Semiahmoo in Whatcom County, was the meeting point of the Canadian/U.S. rail traffic. It was designated as a Chinese Port of Entry for immigrants coming by ship to Vancouver and then to mining and logging camps in the northwestern U.S.) Hoon Owyang said that he went to school until he was twenty years old, then ran a business, the Mow Wah Company, for three years in Heong Shan (1899-1901, now Zhongshan) where he sold Chinese merchandise. Then he went to Canton (now Guangzhou), and helped run a business called the Yee Lee Company, located on Yan Lan Moon Street. He had a $2,000 interest in this firm, which had $8,000 in capital. In the order admitting Hoon Owyang (the order spelled his name Ao Yong Dai Hoon), inspector in charge H. Edsell noted, "He has been carefully examined as to his former occupation, his financial standing and his intention of admitted to the United States...He offers substantial evidence of his financial standing [he had presented a bank draft for $1,000 and $100 in gold and paper money], and examination of his hands and person indicate that he has never engaged in manual labor. He is therefore admitted." The 1905 photograph that was on the certificate is at left. Click here to see the entire certificate, approximately 3' by 2' unfolded, as it is in the National Archives branch in San Bruno, CA. It had been folded many times and was quite worn, as if Hoon Owyang had to carry it in his pocket all the time. He was admitted to the United States on November 23, 1905, at the age of 27. According to his testimony before a return trip to China in 1916, Hoon Owyang first made his headquarters with the Sang Wah Sang Co. on Jackson Street in San Francisco and shortly after made his way to Courtland, California, looking for business. He "did not find anything to do" and returned to Sang Wah Sang and stayed there until 1907, when he became a member of the firm of Dock Sang Wah Company, also on Jackson Street. Within a year, the company went out of business. In 1909 he became a partner in the Hung Lee Shee store with nine other men. See a guide to the complete records at this page. Hoon Owyang joined the Kwong Chong Chan firm when it organized on November 21, 1911. He worked as a general helper and according to his daughter Louise, also bought and sold fish, caught by local fisherman on the Sacramento River. He also was the calligrapher for the firm and for other community buildings; daughter Louise Owyang and nephew Tommy Sue remember helping him carve the characters once he had drawn them. The Chan family, descendants of other original Kwong Chong Chan partners, currently owns the building where the store was located and was kind enough to give us a tour in 2005. Some of the aunties in the Chan family remember Hoon Owyang well, saying he kept the books for the business and taught them how to use the abacus. Visit this page to see photographs of the store and his calligraphy that remains to this day. In 1916, Hoon Owyang returned to China, where he married Gee Chew Lin (also spelled as Chiu Chew Lin) and then returned to Courtland in 1919. This is Hoon Owyang's Certificate of Identity from when he came back to the United States on February 9, 1919. The interrogation records can be viewed at this site.

Gee Chew Lin Owyang's photograph from when she came to the United States February 9, 1919 is on the left. Questions on Angel Island Because he had arrived earlier and had merchant status, Hoon Owyang had a relatively easy time when he returned in 1919. His wife Gee Chew Lin was asked more questions, as the authorities sought to verify that she was indeed the wife of Hoon Owyang. According to her answers to questions upon her arrival in Angel Island on September 2, 1919 at the age of 34, Gee Chew Lin and Hoon Owyang were married on April 21, 1917. She said that she did not know him until they got married. She said that they had a child in 1918 who died in February, 1919. The Chinese family tree says his name was Yung Son. She also said that she had been married before, to Chan Gay Sung, until he died in Jung Gar Bin village in 1915. They did not have any children. Both before he left for China and upon his arrival again in 1919, Hoon Owyang said he had a child by a previous marriage to Jee Shee, who died on January 15, 1916. They allegedly had one child, Ow Yong Dung Wah, born June 28, 1901, who arrived in the U.S. with Gee Chew Lin Owyang. Dung Wah was a "paper son" and not a real son - he actually was Hoon Owyang's nephew. For more information on the paper son activity necessitated by the 1882 and beyond Chinese Exclusion Acts, the first laws of the United States to restrict immigration based on country of origin, visit the thorough website of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation or writer/performer Byron Yee's site. Hoon and Gee Chew Lin Owyang had six children in the United States. They were Mary (Pon), born in 1920, William (1921), Margaret (Chow, 1923), John (1925), Louise (1927), and Esther (Din, 1929). Gee Chew Lin Owyang brought up the six children but unfortunately died in 1934 at the young age of 49. In the 1920's and until World War II, the family lived in Courtland, making a living during the Depression. Daughter Louise remembers that Hoon Owyang would buy fish along the Sacramento River from fishermen and then sell them in the nearby towns such as Locke and their home town of Courtland. He also continued to work in the Kwong Chan Co. store and worked other jobs In a little-known shameful episode of California history, Asian children in the area, including the Owyang family, had to go to a segregated school, the Bates Oriental School According to a National Park Service Web site, In August 1921, the California legislature amended the School Law of California so that "The governing body of a school district shall have power to exclude children of filthy or vicious habits, or children suffering from contagious or infectious diseases, and also to establish separate schools for Indian children and for children of Chinese, Japanese or Mongolian parentage. When such schools are established, Indian children or children of Chinese, Japanese or Mongolian parentage must not be admitted into any other school." Note the association of Asian and Indian students with diseased and filthy children. During World War II, the family moved to San Diego, where Hoon Owyang and some of his children worked in Peking Restaurant. Hoon Owyang returned to China after World War II and was got remarried around 1948. He and his new wife had a daughter. Shortly after the Communist takeover in 1949, he returned to the U.S., and sadly, he never was able to reunite with his new wife and children in the United States or China. The repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Acts in 1943 finally allowed Chinese immigrants to become citizens and established a quota of only 105 immigrants from China each year. After the war, Congress passed a bill allowing spouses of American citizens or those who served in the US military during World War II to immigrate, without regard to this quota. Hoon Owyang, over 65 years old at this time, did not serve in the armed forces and knew little English so did not become a citizen. Who knows what he knew about the immigration laws, but it is possible he saw other Chinese from America bringing back spouses from China and hoped to do the same. According to Bill Greene, archives specialist at the National Archives center in San Bruno, California, "I think your grandfather was in an impossible situation. He was able to travel and return under section "4B" of the Immigration Act of 1924 because he was an 'immigrant previously lawfully admitted to the United States.' Luckily he first arrived in the U.S. before immigration visas were required. His second wife and daughter had never been admitted to the U.S. before so they could not enter without obtaining a "quota immigration visa." The China quota was fixed at 105 per year between 1943 and 1965 (it went to 20,000 in 1965). Half of the quota visas were reserved for the parents of U.S. citizens. The remaining visa slots were available for the spouses and minor children of lawful permanent resident aliens. The odds of getting an immigration visa to emigrate from China in those years were obviously very poor. If he had become a naturalized U.S. citizen he would have had a much better chance of getting them to the U.S. as "non-quota" immigrants. Spouses and minor children of naturalized citizens were not subject to the annual quota limitation. Naturalization was not an easy process - some proficiency in English was required and all applicants had to pass a citizenship test. This was probably quite daunting for many people - especially older residents." Later, the family moved to West Street in Oakland and then to other neighborhoods in that city. On October 27, 1963, Hoon Owyang passed away in Oakland. In 2006, Grant followed in the footsteps of Aunt Mary (1986) and Uncle Bill (1991) and journeyed to Dai Liang village, along with over twenty distant Owyang relatives - fifth to seventh cousins, up to twice removed!. There he met his step-grandmother, her daughter, and her grandchildren. It was an amazing experience.

|